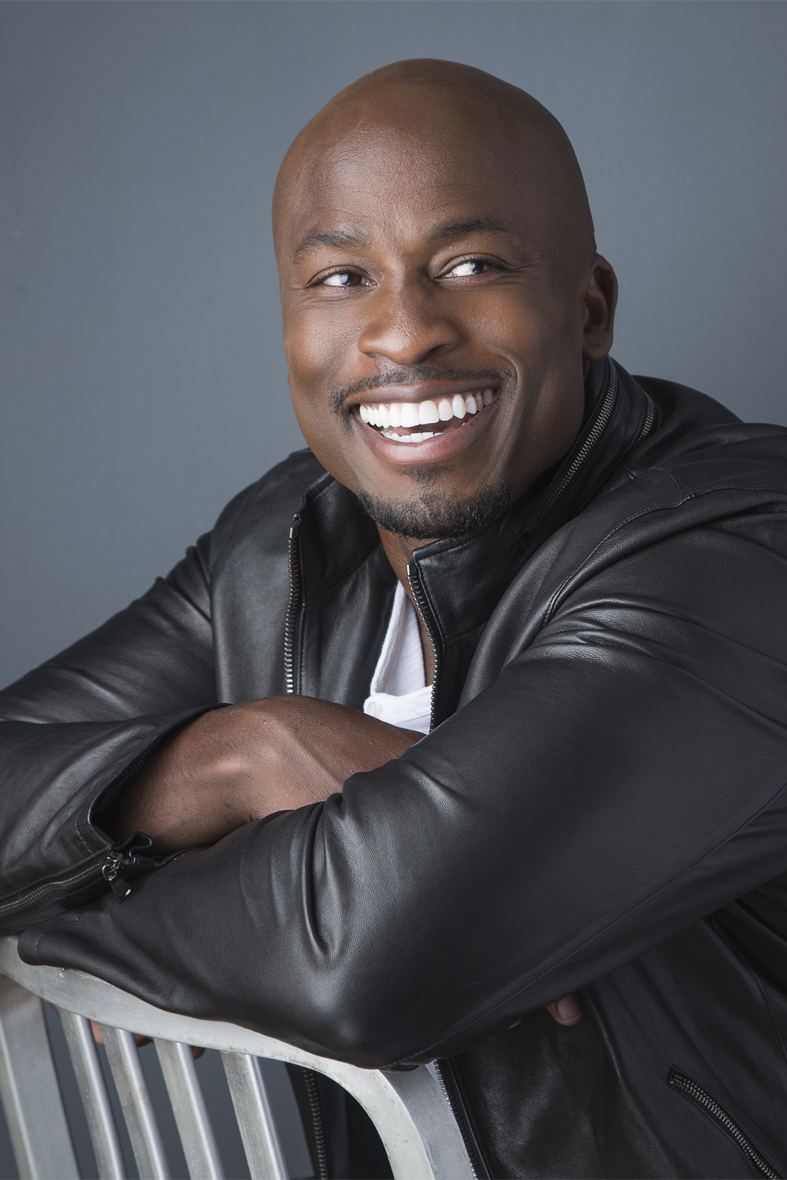

Interview with Akbar Oluwakemi-Idowu Gbajabiamila

Akbar Oluwakemi-Idowu Gbajabiamila. What a distinctive name for a man of great distinction. You’ve probably seen him, host-ing American Ninja Warrior or playing foot-ball for the Raiders, the Chargers, or the Dolphins. If you have, you know that he’s a big guy (6 feet and 6 inches) and very fit. What you may not know is that it was not always thus. It wasn’t unusual for Akbar to have to explain his name during his childhood, an issue which persists today. In one of his father’s languages, Arabic, Akbar means “great.” His last name is based on his father’s dad, who was seven feet tall and a highly respected man in his Nigerian village. Akbar’s last name means “big man come save me,” which didn’t necessarily fit Akbar during the early years of his life. He was tall, but hadn’t yet come into his power.

Growing up in South Central Los Angeles (a.k.a. the Crenshaw District or Leimert Park), he was, of course, always a big kid. But, not surprisingly, height does not al-ways come with coordination at a young age. Akbar was no exception to that rule. His grammar school and even some of his middle school experiences on the playground were not the stuff of dreams (at least, not the good kind). First at Dublin (name then changed to Tom Bradley) Elementary then to Audubon Junior High, he wasn’t the first kid picked to play ball. In fact, if it weren’t for friend Bran-don French—a child athlete who chose Ak-bar for his teams—he might have been the most fit benchwarmer yet. But play he did, and he was so motivated that he got better and better so that, when he was at Crenshaw High, he played on the school’s basketball team. Like his older brother (by three years) Kabeer, he tried football and was pretty good at it; but, he still thought that basketball might be his ticket to big-time sports. When the end of high school drew near, Akbar did get one offer, of a basketball scholarship … and five scholarship offers for football.

Sports was not always foremost on Akbar’s mind, however. Growing up as a first-generation American—his mother, Bolatito (which means “how joy sanctifies me” in her native language), and father, Mustapha (which is another name for Muhammad, and in his native language means “chosen, selected, appointed, preferred”) had emigrated from Nigeria, mom in 1969 and dad in 1974—had its challenges.

His father lost a brother in the Nigerian-Biafra war in the late 1960s and decided to move to America. He was an educated man, who spoke three languages (Arabic, the Nigerian dialect Yoruba, and English) and who planned to be an architect. He was about to enter the market when technology began re-placing drafters with computer-assisted de-vices, so he ended up starting and running a plumbing company, his main career for his adult life. His mother was bilingual (Yoruba and English) and a serial entrepreneur, owning, running a beauty shop, and work-ing in real estate and sundry other matters.

To the family, education was paramount. Although approved, athletics were not seen as the children’s pass to the big time; so, Akbar and his six siblings strove hard in school and did well. His parents emphasized the “power of the pen,” focusing on the abilities to think deeply, speak well, and write convincingly. Mustapha and Bolatito’s parenting style mandated that kids were at school or at home unless they were play-ing sports—the only three approved activities—so academics and athletics became Akbar’s two main interests.

Sports became Akbar’s therapy, a dreamland in which mostly good existed. He visualized him-self like Rocky Balboa, overcoming the odds to achieve success. The drive that served him well in his childhood has benefitted him ever since. And he internalized his father’s frequent admonition: “You’ve got to burn your candle!” Most of you who have heard candle metaphors know that you can’t burn them at both ends, but Akbar’s father used the burning candle to illustrate that a candle not being burned accomplishes nothing.

But even academic and athletic prowess didn’t make up for the feelings of being different, which came from being a first-generation American whose family still followed Nigerian customs, especially wearing of Nigerian-style clothing to school. At a time of life when kids can pick on others just based on something as superficial as style of dress, Akbar and his siblings were teased about their fashion sense; but, they continued their adoption of Nigerian clothing and many of their meals were traditional Nigerian foods. Akbar is proud of his Nigerian heritage, but it did cause some strain during his childhood.

When Akbar entered college at San Diego State University, he entered a whole new world. Until then, he had to navigate two worlds—Nigerian and African American—but college added a world which was not as well-known to him, the white world. Until then, Akbar only had one Caucasian teammate on any sport he had played; but at college, with classmates from multiple states and countries, he was exposed to new ways of thinking and being. Fortunately, he also was there with his brother, Kabeer, an upper-classman, who served as a helpful guide in get-ting acclimated. It also helped that Akbar had his SDSU Aztecs football teammates, creating a world within the world in which he was comfort-able as well as successful, red-shirting one year so he actually played six football seasons there. There was great camaraderie among his college football teammates, where one’s race was not the defining issue and his athletic prowess and winning personality won him many friends. Akbar excelled in college, both in academics and foot-ball. When it came time for the next step, he joined the Oakland Raiders in 2003.

Akbar wasn’t drafted. He still was rather new to the game, only picking it up in high school, whereas many pro ballers start playing as children. He joined the Raiders as an un-drafted free agent, playing defensive end, but he was behind three other prime defensive players. True to his “underdogs try harder” mantra, he worked hard at the position and stayed with the team for the 2003, 2004, and 2008 seasons, along with such illustrious teammates as Jerry Rice, Tim Brown, and Bill Romanowski. Being able to spend time with such luminaries—heroes from his child-hood—was a terrific experience for him. He didn’t stay with the Raiders during the intervening years: he played the 2006 season with the San Diego Chargers and the 2007 season with the Miami Dolphins, accomplishing a fairly long career in an industry where the average NFL player’s tenure is two and one-half years.

After Akbar was cut by the Raiders, he decided to try sportscasting. He worked for free, in order to gain the experience, with the San Diego NBC affiliate, covering the SDSU Aztecs’ and the San Diego Chargers’ games. He enjoyed it and, in 2009, was hired by CBS College Sports to cover college games. In 2010, he added television coverage of the Conference USA games and, in 2011, moved to coverage on NBC college sports with the Pac-12 Conference. In 2012, the NFL Network hired him. A year later, he was asked to audition for American Ninja Warrior, where he not only serves as commentator, but also has participated in the obstacle course that is the basis for the show. (He did well). Akbar has helped ANW become one of the top shows on television, averaging over 5,000,000 viewers per season.

To watch Akbar on ANW is to know him: kind, affable, funny, smart. He is very competitive, of course and a fierce advocate for his family (wife Chrystal—they married in 2009—son Elijah, daughter Saheedat, son Nasir, and daughter Naomi). Overcoming the obstacles in his life has defined Akbar as a man with a low tolerance for mediocrity. His kids are achievers, naturally, but he has the typical parental self-questioning of “how much do I push my kids and when do I just support what they’ve chosen to do.” Elijah is in college, but the rest live at home in Southern California and can be seen some days train-ing in the family’s garage/gym or on the street at an impromptu session, with such training aids as a high-stepping obstacle course, reminiscent of a football camp.

Akbar loves to travel and has visited 40 countries so far (out of what, at last count, were 195 countries in the world). He and a football buddy have done a lot of that traveling together and plan to continue a two-to-three-per-year pace as long as they can. Their longest trip so far? Five weeks in Morocco. Akbar was enthralled with the country and amazed that many of the kids whom he met spoke seven languages, no doubt helped by the wide variety of tourists who travelled there. And can there be a better “ambassador” for the United States, especially these days, than a giant, good-natured, friendly, fit, affable, and outgoing guy? Akbar really should hold pub-lic office or be part of our country’s international outreach in some way.

What does he want to be when he grows up? Well, Michael Strahan is a good model for him. Akbar was so impressed by Michael’s successful move from the field to the studio that he called Michael and asked if he could shadow him, something that no one ever had asked of him before. Michael agreed, and Akbar had a terrific time experiencing Michael on the Live With Kelly And Michael show and then on Good Morning America. Akbar is well on his way there, with a successful career in the NFL, impressive television credentials, and now a bestselling book: Everyone Can Be a Ninja: Find Your Inner Warrior and Achieve Your Dreams. It has been very well-received, no doubt by people who “know” Akbar from ANW and want to know more about him. Unlike some well-known people, the more you know about Akbar, the more you’ll like him!Akbar also has served as a brand ambassador for Toyota and will be fulfilling that role in the rescheduled Summer Olympics (officially the Games of the XXXII Olympiad and commonly known as Tokyo 2020, which now commence in July of 2021), which should be a terrific experience that plays to his strengths. He also is in discussion with other brands that want his help with their products, so he’s as busy as he’s ever been.

Looking back at his life so far (he’s only 41 now), he credits the collective experience of his lifetime—of course, Brandon French, but also his innumerable caring and supportive teachers, teammates, friends, coaches and others—for seeing something in him and choosing him as a teammate (in athletics and in “real life”) when others passed him by. Life can be that way: we’re on a path, oftentimes one of our own choosing, then we meet someone or something happens, and there’s a vector of change. Many people’s be-lief in Akbar created such vectors, and Akbar is eternally grateful and humbled by their willing assistance. In fact, Akbar even called Brandon recently, some 30 years after their last conversation, to thank him. They immediately reconnected and had a great call, to no one’s surprise.

Akbar is fond of saying, “Other people can see something in you that you can’t see your-self.” Clearly, that was true of Brandon, and it became true so often of many, many others who came in to his life (some for a short while, others for far longer) that he internalized that sense of success and exudes it in his own charismatic way. Perhaps, though his efforts, growth, and major accomplishments in a life being so well-lived, the true meaning of his name has become “great guy,” as he is known to all who know or even have just met him. And isn’t that the definition of a winner?

Joe Melville

Very cool and inspirational.

Cheers,

Joe